But on the internet, it’s a very one-sided affair.

“This is a meme nation,” says Olena, a Kyiv entrepreneur who manages teams of social media volunteers.

“If this was a war of memes, we would be winning.”

Olena is not her real name. Due to the sensitive nature of the work she and her teams carry out on behalf of Ukraine’s defence ministry, she has asked to remain anonymous.

Her teams work round-the-clock, reacting within hours to news from around the country, producing punchy videos, often set to music, for the ministry’s audiences at home and abroad.

Just as Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky tailors speeches to foreign parliaments to take account of local history, culture and sensibility, so Olena’s five-strong international team target their messages.

A June video thanking Britain for its military assistance featured the music of Gustav Holst and The Clash, with glimpses of Shakespeare, David Bowie, Lewis Hamilton and a montage of British-supplied anti-tank weapons in action.

More recently, French President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to supply Caesar self-propelled guns was greeted with a video which declared: “Romantic gestures take many forms”.

Images of red roses, chocolates, the Paris skyline, followed by the guns in action, were set – perhaps inevitably – to the sound of Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s breathless Je T’aime Moi Non Plus.

With nods to a Macron-Zelensky bromance, it was suggestive and thoroughly tongue-in-cheek.

Olena says one of her favourite “thank you” videos praised Sweden for its value-for-money investment in Ukraine: $20,000 (£17,900) Carl Gustav rocket launchers, capable of knocking out Russian T-90 tanks worth $4.5m.

The tune? You guessed it: Abba’s Money, Money, Money.

Thanks to the team’s efforts, the defence ministry’s Twitter feed now has 1.5m followers around the world. Some of the videos have been viewed more than a million times.

Their most successful video, released in August after several mysterious attacks on Russian targets in annexed Crimea, has racked up 2.2m views. It mocked Russians for going on holiday on the peninsula and was set to the Bananarama song Cruel Summer.

“The main idea is to speak to the international audience and show that Ukraine is actually capable of winning,” she says. “Because nobody wants to invest in losers.”

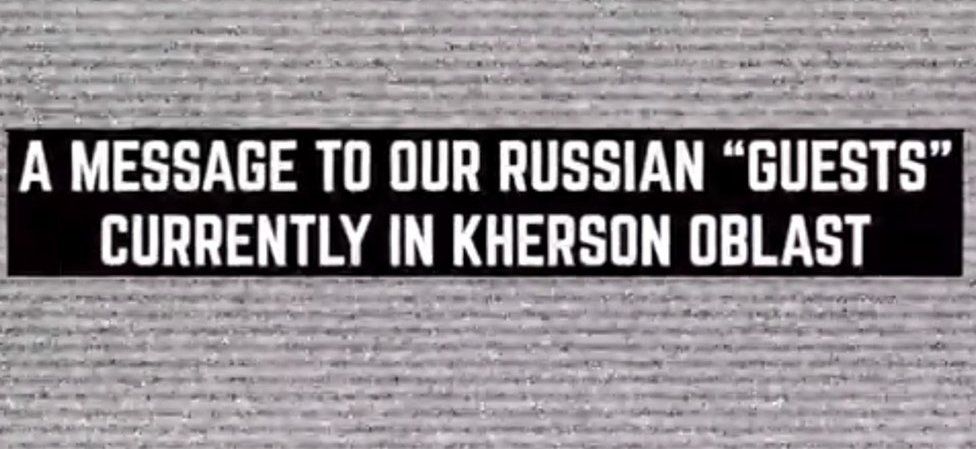

But another of Olena’s teams carries out more subversive work, designed to highlight Russian losses and demoralise Ukraine’s invaders.

Targeting Russian audience

With a wealth of videos depicting Russian military setbacks being posted on social media platforms, the team is not short of material. But they’ve learned through trial and error what works and what doesn’t.

“We started displaying dead Russian bodies,” Olena says. “And then we realised that it actually didn’t work. It only united them against us.”

The team then tried to appeal to the consciences of Russian soldiers by showing images of dead Ukrainian civilians. Again, it seemed to fall on deaf ears.

“We realised they were actually proud of it. They were not condemning this at all,” she says. “We realised that we have to do this in a much more sophisticated way.”

Now the volunteers scrutinise Russian social media platforms, looking to press buttons and probe weaknesses in specific parts of the country.

“If you do it in Saratov you have to know what’s going on in Saratov,” Olena says. “If you do it in Nizhny Novgorod, you have to know what’s going on in Nizhny Novgorod.”

It’s extremely hard to gauge the impact this work is having, but Vladimir Putin’s recent partial mobilisation has given the volunteers lots of material to work with.

“We were waiting for the mobilisation,” Olena says. “We knew that it would be very demoralising for them.”

The single richest seam of material is to be found on the messaging service Telegram. Olena calls it “the Wild Wild West”.

The volunteers providing material for the defence ministry are just a small part of a vast, vibrant, fiercely patriotic and wildly irreverent community reacting to events on the ground, sometimes with amazing speed.

Scores of Telegram channels attract huge numbers of followers.

One, called “Ukrainian Offensive”, has 96,485 followers. Its slogan is “fighting on the civil-meme frontlines of the information war since 2014.”

It provides a diet of military updates, out-and-out trolling of Moscow and occasional digs at Western media coverage (including the BBC).

Like most other channels, it doesn’t shy away from showing suffering, including footage of dead or dying Russian soldiers.

The recent explosion on Russia’s Kerch Bridge, linking Russia with occupied Crimea, triggered a tidal wave of videos, jokes and memes as Ukraine’s internet army celebrated wildly.

But the country didn’t turn into a nation of digital ninjas overnight. Eight years of war in the eastern Donbas region has given people lots of time to hone their skills, from countering disinformation to circulating humorous content designed to boost morale.

The current social media environment, says Ihor Solovey, head of Ukraine’s Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security, reflects a rare convergence of official and popular sentiment.

“We’re witnessing perhaps the first time in history when civil society trusts the state and is helping it,” he told me.

“The armed forces do their own thing, while society is creating content, memes, creative works on their own. Because everyone feels responsible for their own future.”

What, if anything, is Russia throwing back at Ukraine?

Strangely, given Russia’s reputation for troll farms and shady scammers with alleged links to the Kremlin, the answer seems to be: not much.

Earlier this month, two well-known Russian pranksters did manage to con Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba into thinking he was talking to a former US ambassador to Moscow, Michael McFaul.

Excerpts were broadcast on Russian state media, in which Mr Kuleba appeared to admit that Ukraine was responsible for recent attacks in Crimea and Russia – although the prank was conducted before the 8 October Kerch Bridge explosion.

But if Russia does have a similarly inventive internet army, Olena says she has seen little sign of it.

“Russians haven’t managed to come up with anything interesting,” she says. “No humour, no beauty. Not even pain. No compassion.”