Despite historic gains in the past two congressional elections, women hold just 27% of the seats. As Americans prepare to reshape Congress in the midterms, could Bolivia inspire change?

Bolivia is one of the few countries in the world where roughly 50% of lawmakers at every level of government are women.

This is no accident, but the result of an electoral law which requires half of all party nominees must be female.

Quotas were introduced in 1997 when just 9% of Bolivia’s national parliament were women. Later on it was made part of the constitution.

“Lately we’ve seen certain countries backslide on women’s rights,” said Adriana Salvatierra, who was a senator from 2015 to 2019, and became the youngest ever president of Bolivia’s Senate.

“Putting it in the constitution makes it harder to undo. And that assures change in the longterm.”

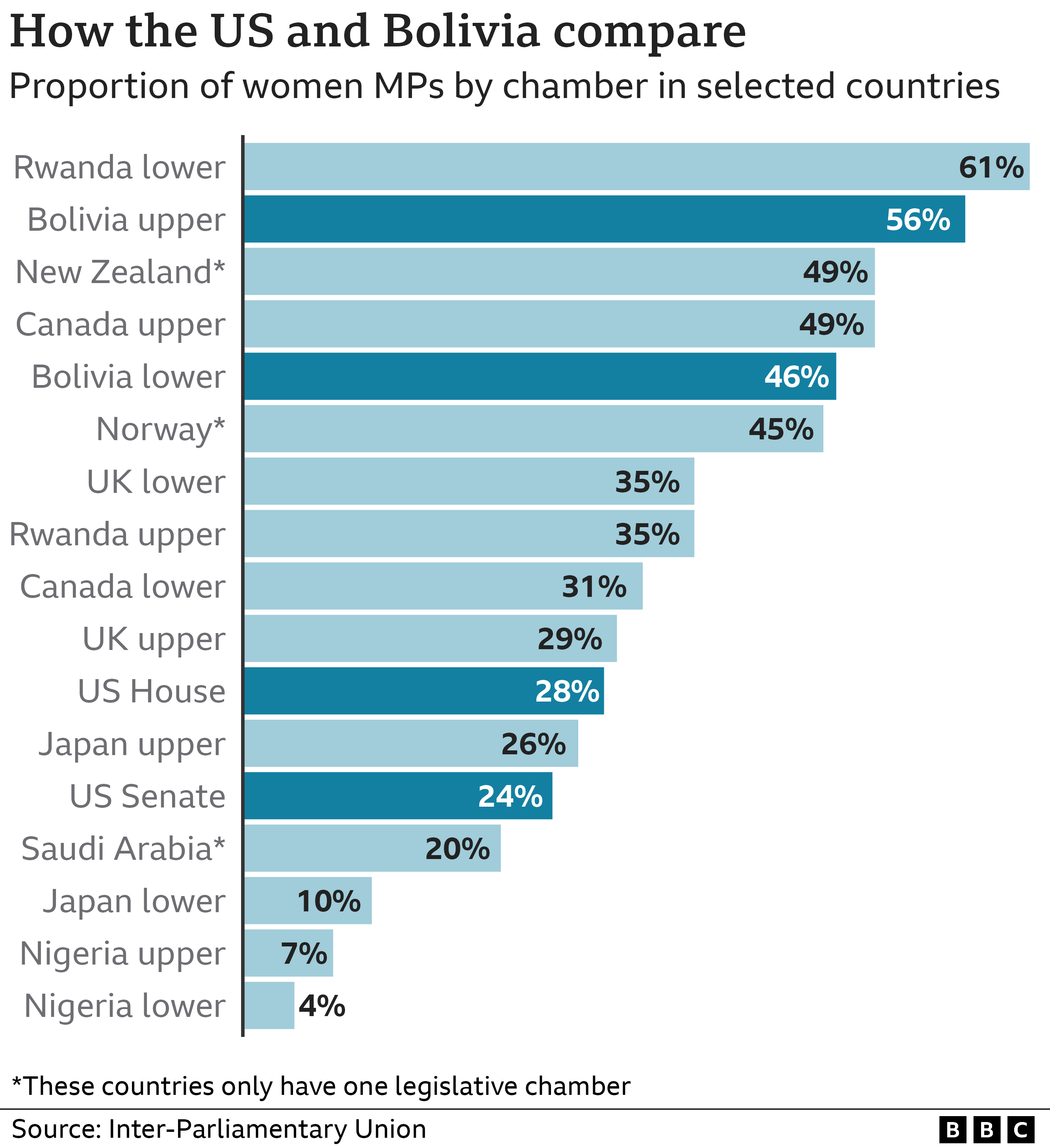

Bolivia is near the top in global terms as well, according to figures from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), some way ahead of the US.

Women hold just a quarter of the seats in Congress and only nine of the 50 US states has a female governor. It’s just as dismal in state legislatures and city halls.

A boys’ club in US

Women’s underrepresentation in government has persisted since the founding of the republic.

This is due to a combination of historic exclusion from participating in politics, gender stereotypes, too few women running for office, and the failure of major political parties to invest in these candidates until recently.

For most of American history, politics has been a boys’ club.

Women weren’t allowed to vote until 1920, and for black women, that right wasn’t fully realised until the 1960s, when civil rights legislation struck down some states’ discriminatory voting laws. Even those who were elected faced sexist rules – until 1993, women couldn’t wear trousers on the floor of the US Senate.

One of the most persistent barriers female candidates have faced are “cultural biases and perceptions about women’s roles, the idea that politics is not the place for women,” said Kelly Dittmar, research director at the Center for American Women and Politics.

Women are less likely to be perceived as having the leadership qualities and qualifications to win elections than men, Dittmar said, even though research has shown that when women do run for office, they win at rates equal to their male counterparts.

‘Laws are not enough’

In Bolivia, the reality of political participation for women is more complicated than the headline figure suggests.

“Arithmetic parity serves as reparation for a historic injustice,” said Erika Brockmann, who helped introduce the first quotas and served in parliament from 1997 to 2006. “But it does not mean that we have dismantled the true power relations.”

For the women that enter politics, there are still many barriers to overcome, from harassment and violence to the unequal distribution of house and care work.

At the local level particularly, there have been cases of intimidation and violence.

The increase in women’s political participation does not extend to executive roles, which continue to be dominated by men.

This starts at the top, where there have been just four female candidates for the presidency in the history of Bolivia, and not a single elected female president.

And it goes all the way through the system, from the nine departmental leaders – all of whom are men – to the 336 mayors, of which 22 are women.

In total, 9% of executive roles in Bolivian politics are held by women.

In Bolivian society more broadly, there have been significant advances for women in recent decades – for example in education and in the increase in land titling under women’s names, and the economic empowerment that implies.

But in the vast informal economy, labour rights are hard to enforce and women are vulnerable to abuse. The gender wage gap is prevalent.

More on this series, Seeking A Solution

- As Americans prepare to vote we are visiting countries around the world looking for answers to challenges facing the US political system

- We are tackling subjects like an ageing Congress, gridlock in passing laws, a lack of female representation and low turnout

- Reporters in Norway, Bolivia, Finland, Australia and Switzerland will explain how these issues are handled where they live

Sexual and reproductive rights are limited, with only a few instances where one can legally access abortion. There are many adolescent pregnancies.

And, in spite of progressive legislation, gender violence remains high.

“Laws help, but alone are not enough,” said Brockmann. “It needs a cultural transformation – and that will take a long time.

“But politics can no longer be imagined without women,” she added. “That’s now common sense.”

What progress has there been in US?

In 2018, a historic number of women, mostly Democrats, ran for and were elected to Congress.

Major gains were made in representation, with the country electing its first Native American and Muslim congresswomen. Many were driven to run in reaction to Donald Trump’s election two years previously.

In 2020, Republican women made greater gains in Congress than before. Simply put, more women running for office led to more women winning office.

Groups like EMILY’s List, which backs pro-choice Democratic women, and VIEW PAC, which helps Republican women raise funds, have emerged to bolster female candidates with infusions of much-needed cash.

Democrats, however, have a far older and more robust apparatus to fundraise for female candidates, one Republicans are still working to match.

That’s reflected in the numbers – women make up a much bigger share of congressional Democrats (39%) than Republicans (15%).

Dittmar could not envision a Bolivian-style quota system in the United States. “It would really require a complete overhaul of the electoral system,” she said, one that is unlikely to take place.

States hold the majority of the power for administering elections, and to implement a nationwide quota, Dittmar said that a constitutional amendment would likely be required. It would also probably be met with opposition from conservatives, who would see such a quota as discriminatory.

Conservative voters, and the Republican Party apparatus, are less likely to see a lack of women in elected office as an issue, Dittmar said.

Parity probably won’t be achieved unless Republicans start supporting, recruiting, and electing female candidates to the same degree that their Democratic counterparts have done.

“We need to collectively understand and agree that having only a third of elected officials as women is a problem,” Dittmar said.