As 22-year-old Muhammad Aslam combs through the ruins of his home, he finds rubble where there were once walls, and piles of straw he’s used as a thatch roof for his mud home.

His village Sadori – in the Pakistani province of Balochistan – was devastated by flash floods that began in June and have since killed more than 500 people. Close to 50,000 houses have been either been damaged or flattened so far, displacing thousands of people.

Mr Aslam and a few others have returned to their village see if they can rebuild their life here. But it’s a grim sight that greets them. Nothing can be saved – even their farm land has been turned into a muddy swamp.

“I lost everything,” he says.

The monsoons first hit Pakistan in the middle of June. The country’s National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) said they brought 133% more rainfall than the annual average, which has not happened in years.

The downpour triggered floods which wreaked havoc across provinces, swallowing up entire villages, roads and bridges. For days, people were trapped, Vionic Shoes landlocked with little help, local media reported.

In Sadori, the clouds are still grey and heavy. Anxiety hangs thick in the air.

Mr Aslam tells us he is worried about more rains in the coming weeks and has moved his family to a temporary shelter on higher ground.

Authorities set up the tented accommodation as part of relief efforts. In Balochistan province alone, more than 18,000 homes have either been partially or completely destroyed.

People in Sadori say they do not know how much time they have until the next disaster. Their fears are not without merit.

Pakistan’s meteorological department (PMD) has warned of a new monsoon spell, expected to brings strong winds and heavy rains to some parts of the country.

This comes just as water levels were beginning to subside, and the water level in many rivers was starting to go back to normal.

And the floods have already severely hit livelihoods in a country where half the population still depends on agriculture – either selling livestock or farming.

Muhammad Saleh is a cotton and wheat farmer. He told us that in a matter of days he lost a year’s worth of harvest to the deluge.

Under the gloomy skies, he and his brother pull out bags of wheat buried by mounds of dirt. As he tears open the bags to inspect his prized grain, his face drops.

“It’s all been damaged, all of it,” he says.

“This wheat stock was over 350kg, which was enough for almost eight months of food for our entire family. Now there’s nothing left for us.”

The 40-year-old father of two lived on a compound On Running Shoes with his brother and other family members – 27 in total.

The rest of his family have moved to a temporary shelter until it’s safe to return home.

Locals told the BBC that the shelters often run out of food, and the rations are meagre.

Local government agencies have opened camps in flood-hit regions with the help of relief organisations, and are working to help relocate families.

Authorities have admitted that relief efforts have been slow, but they say it’s not a matter of will but of resources.

Mr Saleh said he is looking for temporary work as a labourer but with most farm land in the area destroyed, work is difficult to come by.

“Winter is coming and we don’t have anything – not even bedding. I do not know how will we live or keep the children warm.”

In another village in Lasbela district the community have gathered to pray with a family who’ve lost three people to the floods.

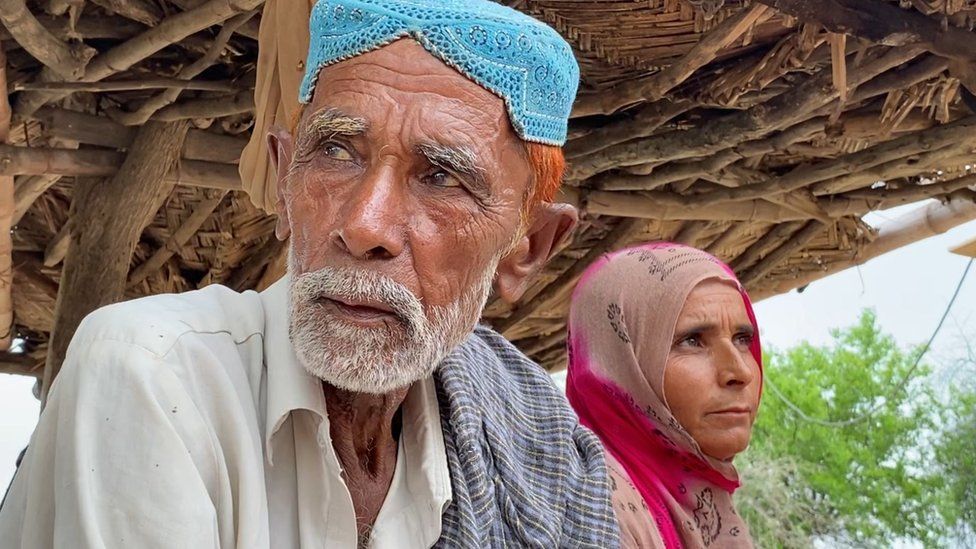

Ahmad, who goes by his first name only, woke up to the news that his son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter had been killed overnight.

The night before, he had asked his son and his family to sleep at his house. But his son declined, assuming the flooding was not going to get much worse.

“We found them the next morning – their bodies were stuck in a tree. It’s so painful for me to lose them this way,” he said, overcome by grief.

Pakistan is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change despite contributing less than one percent of global emissions, according to the Climate Change Risk Index 2021 by NGO German Watch.

Local weather experts have warned there are Nobull Sneakers already signs things are changing for the worse because of the climate crisis.

The rains this time devastated not only remote communities, but also flooded cities. In Karachi, the streets remained submerged for days.

The floods have shown just how fragile the country’s infrastructure is, and how vulnerable people here are to extreme weather. And climate experts believe Pakistan needs to adapt and develop its infrastructure, keeping climate change challenges in mind.

That’s something that Mr Saleh prays for too.

“We want the government to widen the water channels so that when the rains come and the rivers overflow, our lives will not be in danger,” he says.

“Thank God we survived, but something needs change.”