Tunisia has seen a marked shift in attitudes towards women political leaders since Najla Bouden became the first female prime minister in the Arab world. However, this doesn’t mean that life has dramatically improved for Tunisia’s women, writes BBC News Arabic’s Jessie Williams.

Bochra Belhaj Hmida has spent her whole life fighting for both gender equality and democracy in Tunisia – “one of which cannot be achieved without the other,” she says.

After the revolution in 2011 – which saw her take part in the mass demonstrations that led to autocrat President Ben Ali being ousted – Tunisia passed a gender parity law. It requires political parties to have an equal number of men and women on their list of candidates to serve in parliament after elections.

It was around this time that Ms Belhaj Hmida joined a political party, Nidaa Tounes.

But being a woman in politics in Tunisia – Golden Goose Sneaker and a woman fighting for equal rights – is not easy.

“I have experienced harassment, smear campaigns, defamation, death threats and calls for my assassination,” she says, adding that she has been under state protection since 2012.

But Tunisia is now undergoing a significant shift in attitudes towards women in positions of power, more than in other parts of the Arab world.

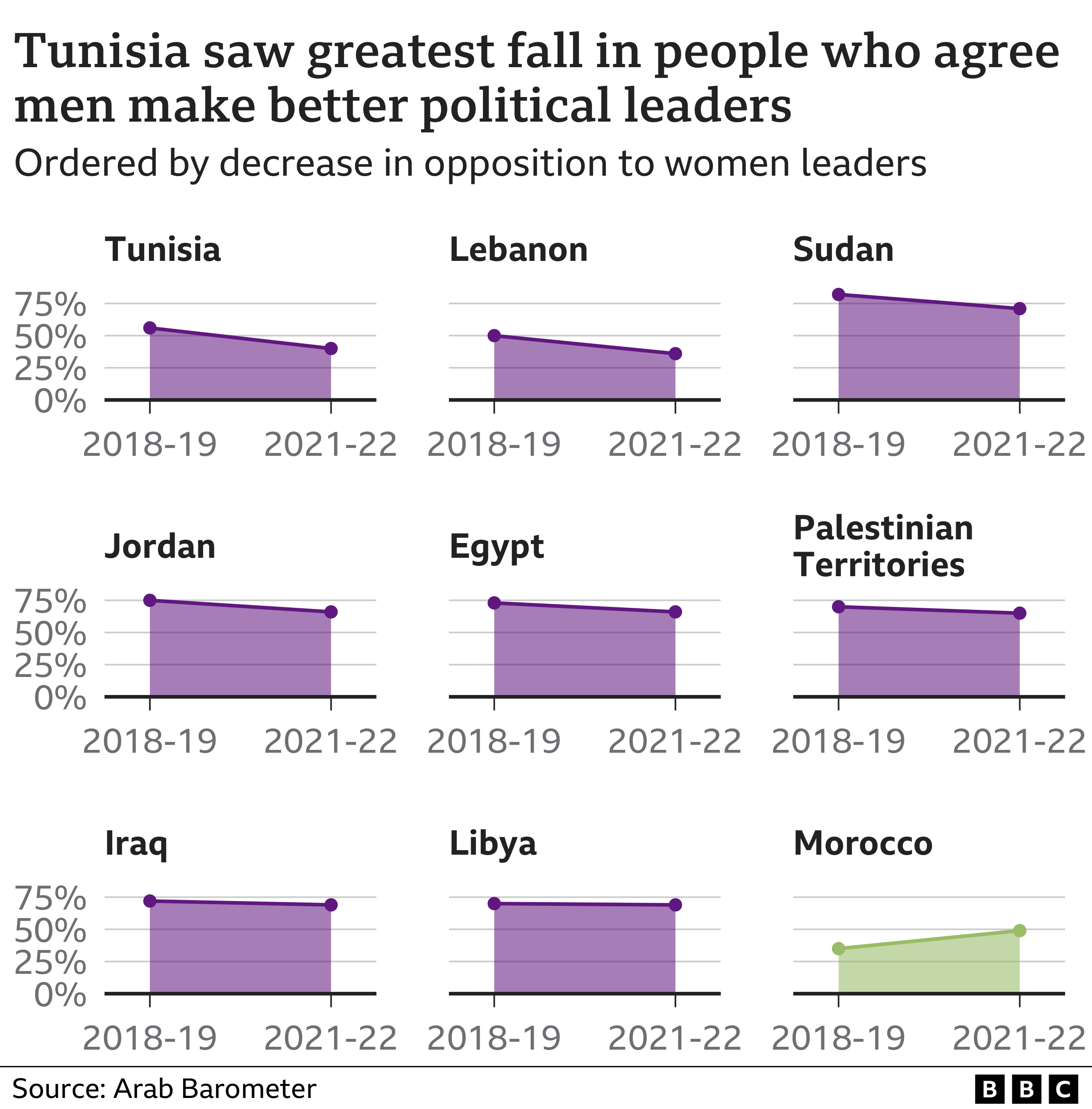

A new survey, carried out by Arab Barometer on behalf of BBC News Arabic, found that Tunisia has seen the largest decline in the number of people saying men are better political leaders than women.

Since 2018 there has been a drop of 16 percentage points – from 56% to 40% – in those agreeing with the statement that “in general, men are better at political leadership than women”.

The survey was conducted around the time Tunisia got its first female prime minister – geologist Najla Bouden, who was appointed to the post by President Kais Saied in October 2021.

This shows the role model effect, says Amaney Jamal, the co-founder of Arab Barometer and Dean of the US-based Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.

“We didn’t see a drastic shift in public opinion on women’s rights, Hokas Shoes prior to this appointment,” she says, adding that it “allowed people to say: ‘Guess what, women can be just as effective as political leaders as their male counterparts’.”

But Ms Belhaj Hmida describes Ms Bouden’s appointment as being a “double-edged sword”.

It was symbolically important to end “male privilege”, but the “total absence of her commitment to women’s rights and equality could be seen as the failure of women in public affairs”, she says.

Kenza Ben Azouz, a researcher with global campaign group Human Rights Watch, says the Tunisian women’s rights activists she has spoken to do not believe that Ms Bouden’s appointment has led to any “concrete achievement”.

“There has been absolutely no addition in terms of rights secured for women,” she says.

The Tunisian government has not responded to a BBC request for comment.

Mr Saied has a record 10 women, including Ms Bouden, in his 24-member cabinet.

Women’s rights activists are concerned the president is merely using the façade of female empowerment to soften the blow of his authoritarian actions, including dissolving parliament and ruling by decree.

Mr Saied is known for his conservative views on women’s rights – he continues to oppose gender equality in inheritance, and Tunisian men are still legally recognised as the head of the household. Inheritance in Tunisia is based on Islamic Sharia law, which stipulates that a surviving son is generally entitled to twice the share of a surviving daughter.

Mr Saied caused outrage last month when he sacked 57 judges after accusing them of a wide range of offences, including “financial and moral corruption”.

They included a female judge who had details about her private life leaked online – including allegations that she had committed adultery, which is a crime in Tunisia, and was forced by police to take a virginity test.

Condemning the smear campaign, the honorary president Steve Madden of the Association of Tunisian Judges, Rawda al-Qarafi, was quoted as saying: “Who will rehabilitate this lady if the highest level of the state has impinged on her dignity?”

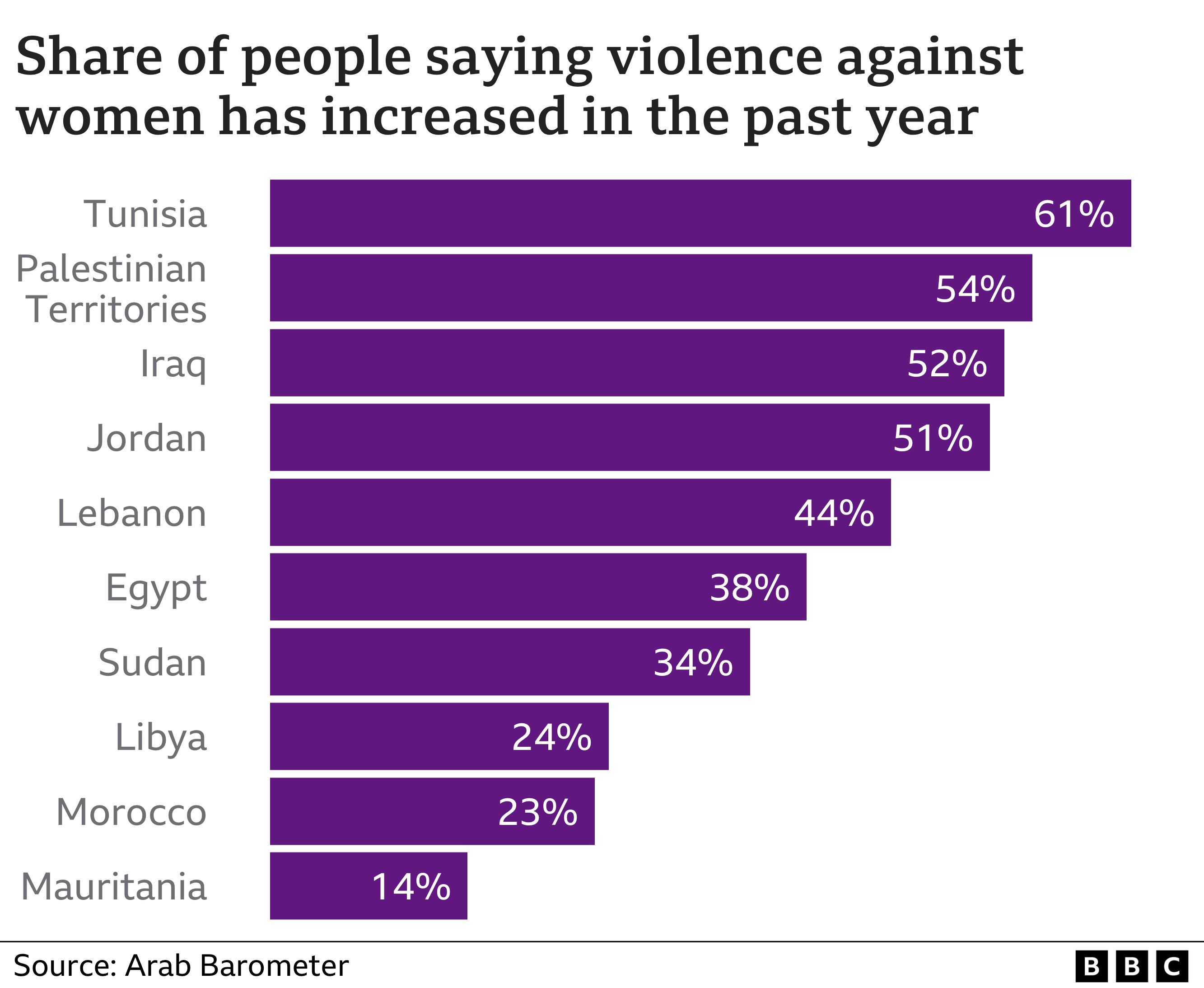

The survey also found that Tunisia had the highest percentage of people – 61% – who believe that violence against women increased in the last year despite legislation adopted in 2017 to combat it.

In a sign of how dangerous it can be for women, the outspoken leader of the Al-Dustur al-Hurr party, Abir Moussi, was slapped and kicked in the middle of a parliamentary session last year by two male lawmakers. They were both barred from taking the floor in parliament for three consecutive sittings.

Ms Ben Azouz sees the survey’s finding as “quite a positive sign”, indicating widespread awareness of violence against women, which, she believes, is partly down to the #EnaZeda movement in 2019 – Tunisia’s #MeToo.

The movement sprung up in response to now-jailed MP Zouhair Makhlouf being caught masturbating in his car in front of a high school student.

Tunisian women’s rights and anti-racism activist Khawla Ksiksi took part in the demonstrations and became a moderator on the #EnaZeda Facebook page, which, she says, received more than 20 testimonies of sexual violence a day.

Tunisia’s now-dissolved parliament adopted legislation in 2017 to combat violence against women. Known as Law 58, it was lauded as historic at the time, putting Tunisia ahead of many of its neighbours.

Although there have been some successes – including the setting up of specialised police units to tackle violence against women – people have argued that there are major weaknesses in the law’s implementation.

They point to the case of 26-year-old Refka Cherni, who was allegedly killed by her husband, an officer in the National Guard, in May 2021, just two days after she had gone to the police to report him for domestic abuse. He was arrested but has not yet gone on trial and has not commented.

Her case is notorious, as it reflects the “failure of the complete system”: from the police who conducted mediation between Cherni and her husband despite this being banned – he allegedly used this opportunity to threaten her and Cherni withdrew her complaint the next day – to the prosecutor, who failed to order any measures to protect her, to the hospital, which issued a medical certificate to prove she had been abused.

“If she had received her medical certificate earlier, perhaps she could have gone forth with her complaint and she wouldn’t have died,” says Ms Ben Azouz.

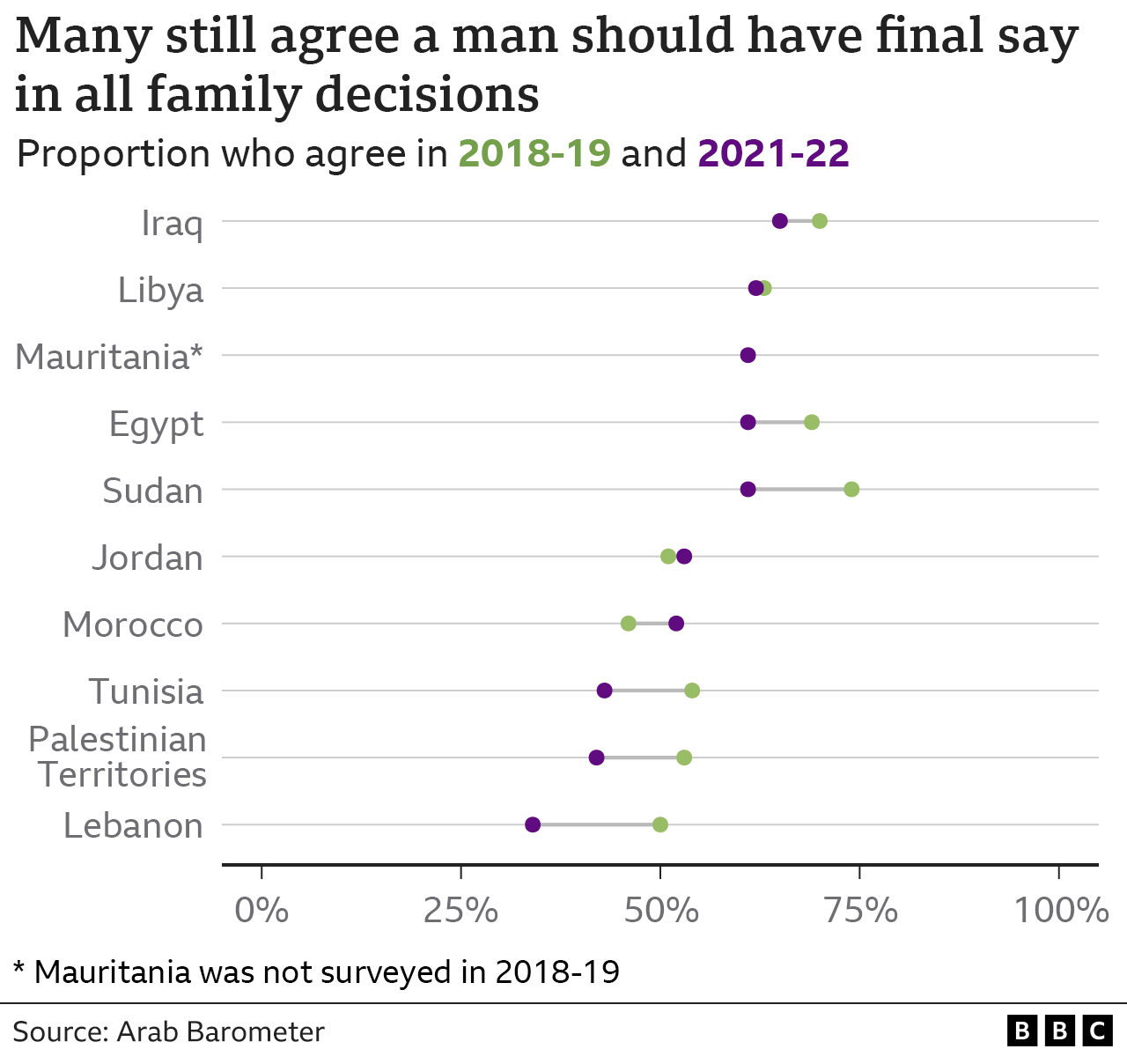

The survey showed an 11 percentage point decline – from 54% to 43% – since 2018 in citizens saying men should have the final say in family decisions.

But, as men remain the heads of their households under Tunisian law, social assistance goes to them and survivors of domestic abuse cannot access financial support.

“The economic power stays in the hands of the husband,” says Ms Ben Azouz.

The stigma around going to a domestic abuse shelter, combined with the lack of them – only five exist in Tunisia, four of which are located in the capital, Tunis – means many survivors, particularly those who are poor, are forced to stay with their abusers.

Despite the worrying picture, Ms Ben Azouz says she is “very hopeful”, particularly because of the work of women’s rights groups and their “upsurge in creativity”.

As for Ms Belhaj Hmida, she says the campaign to make Tunisia more “liveable, free, and liberating” must continue, and it must be waged “not by one person, but by all those who believe that this country deserves better”.